The Act of Cinematic Memory:

On Akira Kurosawa’s Rhapsody in August

By Carlo Rey Lacsamana * August 5, 2021

On Akira Kurosawa’s Rhapsody in August

By Carlo Rey Lacsamana * August 5, 2021

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa

Based on Nabe no naka by Kiyoko Murata

Starring: Sachiko Murase/Kane, Hisashi Igawa/Tadao, Hidetake Yoshioka/Tateo, Toshie Negishi/Yoshie, Richard Gere/Clark

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa

Based on Nabe no naka by Kiyoko Murata

Starring: Sachiko Murase/Kane, Hisashi Igawa/Tadao, Hidetake Yoshioka/Tateo, Toshie Negishi/Yoshie, Richard Gere/Clark

Of all art forms, cinema is the most capable for manifold retrospection. It propels our gaze into a crossroad where the past, present and future, politics and history, personal and collective memory intersect. In watching a (great) film we step into the remembrance of things in time.

Film, through instances of longing, inaugurates and attempts to extend memory. Memory, in a way, is a reinvention of cinema. The compressed account of actual and imagined situations become blurred, fact and metaphor reconciled, memory recovered and recreated.

The 1991 film Rhapsody in August by the legendary Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa (1919-1998) is a film of remembering the legacy of pain and the need to share that pain: an uneasy, disarming, intimate coming to terms with one’s history, legacy—a harking back to the company of the dead. For Kurosawa, filmmaking is an attempt to recover the trail of memory at risk of fading out in the promiscuous bright lights of modern society. In such a time as this obsessed with the narcissistic chaos of the present, emblematic of our social media culture which prefers to leave the past behind.

Film, through instances of longing, inaugurates and attempts to extend memory. Memory, in a way, is a reinvention of cinema. The compressed account of actual and imagined situations become blurred, fact and metaphor reconciled, memory recovered and recreated.

The 1991 film Rhapsody in August by the legendary Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa (1919-1998) is a film of remembering the legacy of pain and the need to share that pain: an uneasy, disarming, intimate coming to terms with one’s history, legacy—a harking back to the company of the dead. For Kurosawa, filmmaking is an attempt to recover the trail of memory at risk of fading out in the promiscuous bright lights of modern society. In such a time as this obsessed with the narcissistic chaos of the present, emblematic of our social media culture which prefers to leave the past behind.

Rhapsody is a story furtively told in three voices of three generations coming together with their disjunctions, apprehensions, longings, and unvoiced questions. The first generation is portrayed by the elderly woman Kane who receives an invitation to Hawaii from her dying older brother. The second, Kane’s two children whose return from a satisfying visit in Hawaii prompts a devastating revelation; and the third, Kane’s grandchildren who spend their summer vacation in her rural home learn about the burdens of history through her memory. At the center of the story is the tragic legacy of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

I mentioned that the story is furtively told because no one voice is central; all voices challenge and nourish each other to hold the narrative. The first wants to keep the memory, the second is eager to forget it, the third struggles to remember. In Kurosawa’s hands the story takes shape in his customary slow-breathing pace, the scenes are elegiac, the dialogue sustained in a kind of attenuated curiosity imbued with calm grief. If memory is the meeting of time’s voices, cinema is the rendezvous of unfolding images.

I mentioned that the story is furtively told because no one voice is central; all voices challenge and nourish each other to hold the narrative. The first wants to keep the memory, the second is eager to forget it, the third struggles to remember. In Kurosawa’s hands the story takes shape in his customary slow-breathing pace, the scenes are elegiac, the dialogue sustained in a kind of attenuated curiosity imbued with calm grief. If memory is the meeting of time’s voices, cinema is the rendezvous of unfolding images.

The film begins with Kane’s grandchildren receiving a letter from their parents vacationing in Hawaii convincing their grandmother to go meet her dying brother, a long lost relative survivor of the bombing whose sole request is to see his sister Kane. To watch a film is as close to receiving a letter from a faraway place. We can only hold our breath as the scenes unfold. Kane hesitates. Given her age and health, she will think about it.

The children take a day trip to Nagasaki, to the place where their grandpa died in the bombing; behind the school where their grandpa worked as a school teacher they discover a makeshift shrine in memory of the tragic bombing. Unable to fathom history, they experience vulnerability and loss, a tender propulsion to remember takes root in them. They visit sites and observe the sculptures donated by foreign countries as a gesture of diplomatic sympathy. The camera closes in on these works of art in which Nagasaki’s legacy of pain is memorialized. Films are in a way memorials. They are moving sculptures of human memory. One of the children laments:

“But nowadays, for most of the people, the atomic bomb is something that happened once upon a time. People are apt to forget even a dreadful event like that.”

The children take a day trip to Nagasaki, to the place where their grandpa died in the bombing; behind the school where their grandpa worked as a school teacher they discover a makeshift shrine in memory of the tragic bombing. Unable to fathom history, they experience vulnerability and loss, a tender propulsion to remember takes root in them. They visit sites and observe the sculptures donated by foreign countries as a gesture of diplomatic sympathy. The camera closes in on these works of art in which Nagasaki’s legacy of pain is memorialized. Films are in a way memorials. They are moving sculptures of human memory. One of the children laments:

“But nowadays, for most of the people, the atomic bomb is something that happened once upon a time. People are apt to forget even a dreadful event like that.”

As is the case the younger generation is locked in historical amnesia. The present pervasive cultural stance is to abandon the inheritance of obligation and remembrance. Because to remember in a way obliges us to inherit a legacy of pain. In Kurosawa’s terms, filmmaking, more than an aesthetic approach, is a moral warding off of the tendency to forget. To watch a film is to enter into the discourse of memory. Cinema partakes in the ritual of witnessing pain. A great film is a disruption of forgetting.

Kane’s two children returns from Hawaii. They find out that Kane has sent a letter to her relatives in Hawaii telling of her decision to finally go right after the memorial service for her husband on the ninth of August—the day the atomic bomb was dropped. The two are mortified. It turns out that they kept the story of their father’s death in the bombing from their American relatives. They argue of the “awkwardness” if their Americanized relatives find out the truth. “Why is it awkward?” asks the third generation. Weighed down by the emotional ambiguities of history, the second generation responds:

“Because Clark (Kane’s nephew played by the dashingly handsome the young Richard Gere) is an American. After he finds out that grandpa was killed by the atom bomb of course, it will make him feel awkward. It is something that is not necessary to mention.”

Kane’s two children returns from Hawaii. They find out that Kane has sent a letter to her relatives in Hawaii telling of her decision to finally go right after the memorial service for her husband on the ninth of August—the day the atomic bomb was dropped. The two are mortified. It turns out that they kept the story of their father’s death in the bombing from their American relatives. They argue of the “awkwardness” if their Americanized relatives find out the truth. “Why is it awkward?” asks the third generation. Weighed down by the emotional ambiguities of history, the second generation responds:

“Because Clark (Kane’s nephew played by the dashingly handsome the young Richard Gere) is an American. After he finds out that grandpa was killed by the atom bomb of course, it will make him feel awkward. It is something that is not necessary to mention.”

If anything, the power of all (great) works of art lies in its capacity to register the bewildering pulse of conscience, to voice out the unmentioned imperatives of collective memory and history. The first generation settles the score. Kane resolves the tension with a voice that has endured the insupportable burden of willful forgetting, indefatigably brave and subtly lonely:

“I don’t see what’s wrong with telling the truth. They did drop the bomb and they resent being reminded of it? If they don’t like it they don’t have to remember it. But I can’t have them pretending ignorance!”

“I don’t see what’s wrong with telling the truth. They did drop the bomb and they resent being reminded of it? If they don’t like it they don’t have to remember it. But I can’t have them pretending ignorance!”

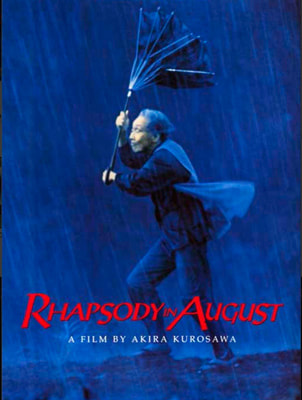

The film ends with an elegiac scene only a master storyteller like Kurosawa could conjure. One stormy morning, Kane in her disoriented state—caused by her age and the inconsolable trauma of the past—braves the rain in search of her husband who perished in Nagasaki, believing that the storm was an atmospheric disturbance caused by the explosion of the bomb. She runs with her waning strength, desperately holding on to a small umbrella as though it was memory itself. Beneath the storm all three generations merge, one chasing after the other, coming together in one constellation of memory and pain.

About Carlo Rey Lacsamana...

Carlo Rey Lacsamana is a Filipino born and raised in Manila, Philippines. Since 2005, he has been living and working in the Tuscan town of Lucca, Italy. He regularly contributes to journals in the Philippines, writing politics, culture, and art. He also writes for a local academic magazine in Tuscany that is published twice a year. His articles have been published in magazines in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Germany, India, and Mexico. Visit his website or follow him on Instagram @carlo_rey_lacsamana.

COPYRIGHT 2012/2021. Paulette Reynolds. All CineMata Movie Madness blog articles, reviews, faux interviews, commentary, and the Cine Mata character are under the sole ownership of Paulette Reynolds. All intellectual and creative rights reserved.