Imitation of Life 1934 :

A Love Story Wrapped in Racism

by Paulette Reynolds

November 9, 2014

A Love Story Wrapped in Racism

by Paulette Reynolds

November 9, 2014

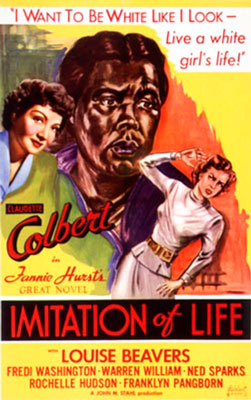

Imitation of Life

1934

Directed by John M. Stahl

Screenplay by William J. Hurlbut; based on Novel by Fannie Hurst

Cinematography Merritt B. Gerstad

Universal Pictures

Starring Claudette Colbert/Beatrice "Bea" Pullam, Louise Beavers/Delilah Johnson, Fredi Washington/Peola Johnson, Warren Williams/Steve Archer, Rochelle Hudson/Jessie Pullman

1934

Directed by John M. Stahl

Screenplay by William J. Hurlbut; based on Novel by Fannie Hurst

Cinematography Merritt B. Gerstad

Universal Pictures

Starring Claudette Colbert/Beatrice "Bea" Pullam, Louise Beavers/Delilah Johnson, Fredi Washington/Peola Johnson, Warren Williams/Steve Archer, Rochelle Hudson/Jessie Pullman

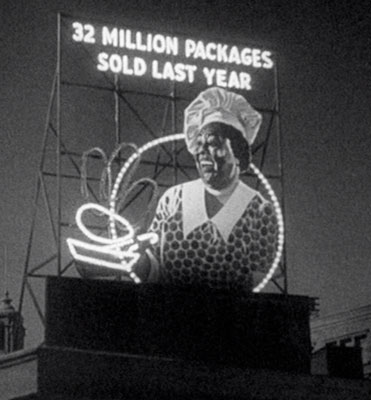

At first glance, Imitation of Life appears to be is a story about race and relationships during the 1930s. Bea Pullman and Delilah Johnson are two single parents, struggling to raise their daughters in the rough world of the Depression, where hunger lingers on every corner. These two independent spirits form a fast friendship, pooling their resources as Bea tries to dream up the perfect business that will rescue them from poverty. Lucky for them, Delilah whips up a breakfast plate of pancakes that eventually spell success for both women.

But I began by saying this was a story about race and relationships, didn't I? Imitation of Life 1934 serves up an interracial lesbian love story, shattering our expectations through the hidden prism of color politics. Shedding conventional roles, this film explores the relationship between Bea, a white single parent, and Delilah, her black counterpart, during a time when social-political changes were straining the status quo for both women, minorities and homosexuals in America.

But what were these societal expectations in 1934? With respect to gender, women were supposed to be devoted wives and loving mothers. Delilah and Bea are single, by choice or circumstance, but Bea focuses most of her energy on managing the business while Delilah plays Mammy to their offspring. This might smack of just the same old racial inequality despite their loyal friendship, yet Imitation of Life uses the role of servitude to mask the deeper devotion that exists between these two women.

But what were these societal expectations in 1934? With respect to gender, women were supposed to be devoted wives and loving mothers. Delilah and Bea are single, by choice or circumstance, but Bea focuses most of her energy on managing the business while Delilah plays Mammy to their offspring. This might smack of just the same old racial inequality despite their loyal friendship, yet Imitation of Life uses the role of servitude to mask the deeper devotion that exists between these two women.

The strongest thread of this film - indeed, in the novel by the same name - is the friendship between Bea and Delilah. Even with the veneer of deference that Delilah offers and that Bea casually accepts, their lives are intertwined by more than economics and girl-talk. On a subterranean level theirs is a friendship that dare not speak its name - at least, not overtly. When Delilah soothes her tired feet and Bea drops everything to help her search for Delilah's wandering daughter, Peola, we realize that their love is exclusive and for life. It's unclear if the general 1934 audience caught the gay subtext, as it was subsumed neatly within the servile veneer that Colbert and Beavers play.

Imitation of Life came at a time when it was vital for society to remind women - especially black women - about the narrow definition of race and class. White Bea Pullman can be rich, living luxuriously upstairs, running the business, while Delilah only gets 20% of the profits from her pancake recipe and lives comfortably downstairs. Delilah and Peola may be well-dressed, but not to the stylish extreme of fashion maven Bea, and to a lesser extent, her daughter, Jessie. As Bea charms and captivates during all a party, Delilah and Peola must look at the guests from a safe distance. On one level, it’s easy to get angry at the inequality that they suffer, especially Peola, who - unlike her mother - has no love interest to turn to for support.

Imitation of Life came at a time when it was vital for society to remind women - especially black women - about the narrow definition of race and class. White Bea Pullman can be rich, living luxuriously upstairs, running the business, while Delilah only gets 20% of the profits from her pancake recipe and lives comfortably downstairs. Delilah and Peola may be well-dressed, but not to the stylish extreme of fashion maven Bea, and to a lesser extent, her daughter, Jessie. As Bea charms and captivates during all a party, Delilah and Peola must look at the guests from a safe distance. On one level, it’s easy to get angry at the inequality that they suffer, especially Peola, who - unlike her mother - has no love interest to turn to for support.

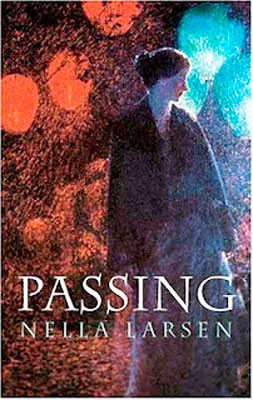

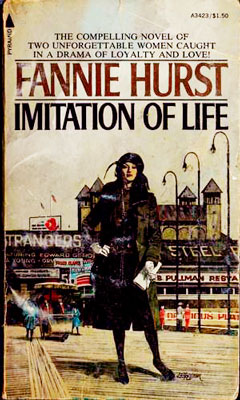

Yet the subject of race is another central theme for all concerned. At a time when over 100,000 light-skinned minorities were passing as white, Imitation of Life acts as the cautionary tale for all second-class citizens yearning to breathe free - even if they have to live a lie. Peola, represents this trend, that was explored in Nella Larsen's 1929 novel, Passing- which bears more than a passing similarity to Fannie Hurst's 1933 blockbuster, Imitation of Life. Larsen was an artist from the Harlem Renaissance movement, and the title of her work referred not only to racial barriers but to those constraints placed on homosexuals of the time.

Here Delilah's role is to teach what White America wants - that Black Americans - and single white women - should know their place. The film painfully develops the rising conflict within Peola and between mother and daughter. Delilah becomes more desperate with each cruel outburst from her daughter, who refuses to accept that she can't pass for white. "Look at me. Am I not white? Isn't that a white girl?", she demands, looking at her reflection in a mirror.

Many scenes of the 1934 film produces a marked visceral response to Louise Beavers stifling mother and Fredi Washington's spiteful offspring. Delilah's hysteria begins to match Peola’s, as she grimly makes it her duty to try to force her into submitting to societal expectations. She instructs Peola to, "Bow your head! You got to learn to take it!"

However, Peola’s genuine feelings for her mother are blocked by Delilah's constant smothering and her own refusal not to let make her own choices. Instead, she hovers at her daughter's elbow, sweetly badgering to accept the racism that surrounds her until Peola finally breaks free.

Here Delilah's role is to teach what White America wants - that Black Americans - and single white women - should know their place. The film painfully develops the rising conflict within Peola and between mother and daughter. Delilah becomes more desperate with each cruel outburst from her daughter, who refuses to accept that she can't pass for white. "Look at me. Am I not white? Isn't that a white girl?", she demands, looking at her reflection in a mirror.

Many scenes of the 1934 film produces a marked visceral response to Louise Beavers stifling mother and Fredi Washington's spiteful offspring. Delilah's hysteria begins to match Peola’s, as she grimly makes it her duty to try to force her into submitting to societal expectations. She instructs Peola to, "Bow your head! You got to learn to take it!"

However, Peola’s genuine feelings for her mother are blocked by Delilah's constant smothering and her own refusal not to let make her own choices. Instead, she hovers at her daughter's elbow, sweetly badgering to accept the racism that surrounds her until Peola finally breaks free.

Beatrice is clueless about Posey's obsession with color, after all, she has none of those concerns. In a world where white women are routinely treated as second-class citizens by men, she's content to show support for Delilah while allowing her daughter, Jessie, to grow up, unfettered by such worries. Instead, her attention is taken up by her romance with Steve Archer - a wonderful man who’s absolutely right for Bea - urbane, sophisticated, and loving every moment of Bea's empowerment. When Jessie returns home from college on a holiday break, Bea convinces him that they must put off telling her about their relationship until Jessie gets to know him. Circumstances take Delilah and Bea off to search for Peola, but Bea suggests that this is a good opportunity for them to get to know each other while she's gone. By the time they return, Jessie has fallen for Steve, mistaking his good-natured banter for romantic foreplay, much to his surprise and displeasure.

Bea halts their engagement, supposedly to buffer Jessie's feelings, but the relief in her voice as she says goodbye signals to understanding viewers that she never wanted to get married in the first place. After all, her heart belongs elsewhere. For the heterosexual 1934 woman, this naturally translated into the freedom coda that was familiar to so many women's films of the era, but the lesbian community knew better. And the married women of that era had just as few choices as Peola, who were expected to quit working for home and hearth.

Bea halts their engagement, supposedly to buffer Jessie's feelings, but the relief in her voice as she says goodbye signals to understanding viewers that she never wanted to get married in the first place. After all, her heart belongs elsewhere. For the heterosexual 1934 woman, this naturally translated into the freedom coda that was familiar to so many women's films of the era, but the lesbian community knew better. And the married women of that era had just as few choices as Peola, who were expected to quit working for home and hearth.

Unable to save her daughter, Delilah promptly dies a glorious death, instructing Bea on her funeral arrangements. There is a revealing moment for Bea as she struggles to realize that she will now have to face life without her lifetime companion. Again, observant viewers will also connect the dots within this short but powerful scene.

As her casket is loaded into the hearse, Peola breaks down and declares to the world that Delilah is her mother. At last, her daughter is forced to accept her third-class status in a future of servitude and inequality. But this moment sparks the opportunity for her to embrace her biracial status in pre-war America. With a new decade just on the horizon, perhaps the biracial Peolas of America could transformed their self-hatred into something separate from the rigid dictates of class and color.

As her casket is loaded into the hearse, Peola breaks down and declares to the world that Delilah is her mother. At last, her daughter is forced to accept her third-class status in a future of servitude and inequality. But this moment sparks the opportunity for her to embrace her biracial status in pre-war America. With a new decade just on the horizon, perhaps the biracial Peolas of America could transformed their self-hatred into something separate from the rigid dictates of class and color.

Imitation of Life 1934 was a showpiece for Claudette Colbert and she sparkles as the optimistic Beatrice Pullman. She has an outfit to match every new crisis and she wears them to the hilt, all fabulously filmed by cinematographer Merritt B. Gerstad. Her role is to float above whatever obstacle is put in front of her, relying on her better half, Delilah, to patiently explain it all. There are many condictions to raise our blood pressure, but the force of Bea and Delilah’s forbidden bond and Delilah and Peola’s conflicted double life commands our sustained attention.

The stars of this story go beyond the black mother and her biracial daughter, as Imitation of Life encourages us to emotionally connect through the generic Mother-Daughter theme. In the 1934 version, Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington (herself biracial) dominate our attention, after all, every woman was a girl (at one time) with a mother who tried to snap the leash, and then we grew up to become a subtle variation of that dynamic for our own daughters. This powerful relationship has spawned countless stories, psychological theories and 12 step programs that immediately allow us to relate with our on-screen counterparts.

The stars of this story go beyond the black mother and her biracial daughter, as Imitation of Life encourages us to emotionally connect through the generic Mother-Daughter theme. In the 1934 version, Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington (herself biracial) dominate our attention, after all, every woman was a girl (at one time) with a mother who tried to snap the leash, and then we grew up to become a subtle variation of that dynamic for our own daughters. This powerful relationship has spawned countless stories, psychological theories and 12 step programs that immediately allow us to relate with our on-screen counterparts.

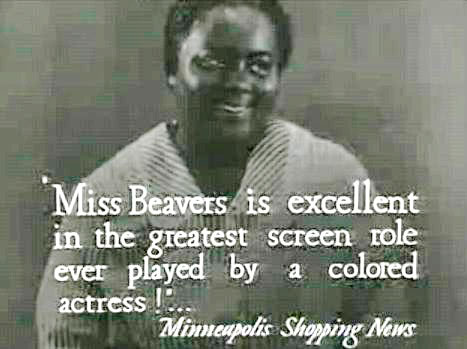

But this familial bond goes further than biology in Imitation of Life, with both the 1934 version and 1959 remake, starring Lana Turner and Juanita Moore. There's no doubt that Beavers and Washington stole the entire film, along with Colbert's runway fashions. Louise Beaver's superbly emotive interpretation matches Fredi Washington's rage every step of the way, and it was a crime that neither of them were nominated with an Oscar for their efforts.

Imitation of Life, circa 1959, repeated the same cinematic magic and netted Oscar nominations for both Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner (who did nab a Golden Globe), but the script changes produced an uneven result. Lana Turner's role was now that of a stage actress and the sub textual love affair, so prominent in the 1934 version, was cut entirely. This left Juanita Moore with the one-dimensional part of the black Mammy servant, yet she was free to explore a more complex relationship with Susan Kohner, who played her daughter. The 1959 remake also pandered to an emerging teen market, by focusing more attention on Sandra Dee and Troy Donahue. Try as Lana, Sandra and Troy might, the film will always belong to the magnificent Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner.

As any film critic will tell you, every viewer sees something different in every film. Much to our delight, Imitation of Life 1934 offers a multi-level viewing experience, one that promises to challenge and entertain us for generations to come.

COPYRIGHT 2012/2016. Paulette Reynolds. All CineMata Movie Madness blog articles, reviews, faux interviews, commentary, and the Cine Mata character are under the sole ownership of Paulette Reynolds. All intellectual and creative rights reserved.